STOUPA and ‘ZORBA THE GREEK’

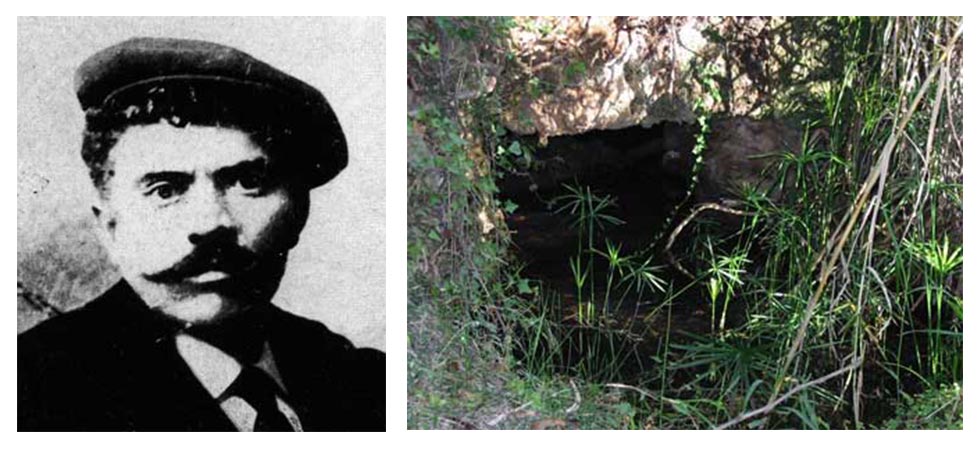

In 1917, a little-known writer called Nikos Kazantzakis arrived in Stoupa from Crete and established a small lignite mining business in the cliffs behind Stoupa at Prastova. He recruited an engineer from northern Greece to help him and so Giorgos Zorbas came to Stoupa – and a legend was born. Zorba was an almost ‘larger than life’ character. At work he was inventive, imaginative and hard working while at leisure he was irrepressible, spontaneous and fond of a drink!

The ground outside the entrance to the mine has been terraced and the entrance has all but disappeared under mud and water and the galleries are flooded. Nearby, against a backdrop of magnificent Cypress trees and surrounded by a veritable jungle of shrubs and trees, stands the two storey building which served as the Company Office and which is now a private house.

The lignite was transported from the mine by trolleys running on a narrow railway down to the cliffs above the sea at Tsirinitsa. Below here, opposite the large rock which forms a small island just offshore, is the narrow rock shelf jutting into the sea which served as the loading dock to take the lignite on board the small boats which carried it to Kalamata. On the cliffs above Tsirinitsa, the lignite was graded by local women and then loaded into trolleys which ran down to the dock on a ‘cable railway’ – a double line of wires which Zorba had designed and built and which provided the inspiration for the device which Zorba was to build later in the novel to bring timber down the mountain to serve as pit-props in the mine.

A short distance south from here, the rugged coastline breaks down to form the sandy cove of Kalogria Beach. On the shelf of rock on the northern side of the beach there are some small bungalows. In Zorbas’ time there was only one small ‘hut’ and this was where he lived during the summer months. Kazantzakis lived on the headland on the opposite side of the beach but his house has also disappeared. On this headland, just beyond the edge of the beach is a small cave and it was here that Kazantzakis set up a table and chair and retreated to read and write in solitude. The beach itself was where Zorbas and some of the mine workers relaxed at the end of a hard day in the mines and where they were sometimes joined by Kazantzakis and his friend, the poet Sekelianos.

In the book, the setting was transposed to Crete but the main character remains, so far as we can tell, the real Zorba. Why else would the book centre on a lignite mining venture that failed, as it did at Stoupa, with an extraordinary character whose name is unchanged? And he certainly was extraordinary. The whole book is a study by the author of this man who was at once simple and complex, loveable and frightening, straightforward and cunning. Every day brought a new revelation or experience for the author and made him think again of all that had become commonplace. He told us as much when he wrote:

He interrogates himself with the same amazement when he sees a man, a tree in blossom, a glass of cold water. Zorba sees everything everyday as if for the first time. We were sitting yesterday in front of the hut. When he had drunk a glass of wine, he turned to me in alarm:

“Now whatever is this red water, boss, just tell me! An old stock grows branches, and at first there’s nothing but a sour bunch of beads hanging down. Time passes, the sun ripens them, they become as sweet as honey, and then they’re called grapes. We trample on them; we extract the juice and put it into casks; it ferments on it’s own, we open it on the feast day of St. John the Drinker, it becomes wine! It’s a miracle! You drink the red juice and, lo and behold, your soul grows big, too big for the old carcass, it challenges God to a fight. Now tell me boss, how does this happen?”

I did not answer. I felt, as I listened to Zorba, that the world was recovering its pristine freshness. All the dulled daily things retained the brightness they had in the beginning, when we came out of the hands of God. Water, women, the stars, bread, returned to their mysterious, primitive origin and the divine whirlwind burst once more upon the air.

His vitality and exuberance constantly amazed Kazantzakis but no more so than when Zorba was happy:

Zorba was dumfounded. He tried hard to understand; he could not believe in such happiness. All at once he was convinced. He rushed towards me and took me by the shoulders.

“Do you dance?” he asked me intensely. “Do you dance?”

“No.”

“No?”

He was flabbergasted and let his arms dangle by his sides.

“Oh well,” he said after a moment. “Then I’ll dance, boss. Sit further away so that I don’t barge into you.”

He made a leap, rushed out of the hut, cast off his shoes, his coat, his vest, rolled his trousers up to his knees and started dancing. His face was still black with coal. The whites of his eyes gleamed. ………………………

“I feel better for that,” he said, after a minute, “as if I had been bled. Now I can talk.”

He went back to the hut, sat in front of the brazier and looked at me with a radiant expression.

“What came over you to make you dance like that?”

“What could I do, boss? My joy was choking me. I had to find some outlet. And what sort of outlet? Words? Pff!”

The book is also full of charming observations and one my favourites is:

Every village has its simpleton, and if one doesn’t exist they invent one to pass the time. Mimiko was the simpleton of this village. …………

“Sit down, Mimiko, have a drink of arrack, so you don’t catch cold!” uncle Anagnosti said, feeling sorry for him. “What’d become of our village if we had no idiot?”

There is an intriguing little mystery connected with the mining enterprise. In the early part of 1917, a group of Germans suddenly arrived in Stoupa. Nobody knew who they were or from where they had come. Rumour had it that they were escaped Prisoners of War but as there were no prison camps in the Peloponnese, this only added to the mystery.

They applied to work at the mine and rented a house in Stoupa where they also did odd jobs such as repairing clocks and watches and making all sorts of wooden toys for the children. They were accepted in the village as pleasant and hard working young men but then one morning they had all mysteriously disappeared. They left all their belongings in the house but no trace was ever seen of them again and rumour and conjecture ran wild. A group like this travelling overland would surely have been seen so the predominant theory was that they had been taken away secretly by submarine.

A police detachment made the eight-hour march from Areopolis to investigate and marched back again none the wiser. The story eventually reached Athens where it was published in the press but the incident remains a mystery to this day.

(Note: Greece was technically Neutral during the war but a very complicated political situation deeply divided the country and the loyalties of the Greeks – the so-called National Schism. The Peloponnese, including the Mani, was (and in many places still is) fiercely Royalist. The King of Greece at this time, Constantine 1, was an honorary Field Marshall in the German Army and married to the sister of Kaiser Willhelm II so the presence of Germans in Stoupa would not have been cause for alarm although it was cause for speculation and rumour. Rumours involving German submarines persisted into late 1917 with stories that they were secretly refuelling with lignite at Stoupa).

In 1946, Kazantzakis published his best-known novel “Zorba the Greek” and the film was released in 1964. All over the world, people were enthralled with the man who epitomised the quintessential Greek character and more than anything else, they were fascinated by his exuberance – especially in the scene where he is compelled by his nature to dance on the beach. This scene, reinforced by the music of Greece’s much beloved composer Mikis Theodorakis, became the icon of what it means to be ‘Greek’. It’s a wonderful story and the inspiration behind it was a man who once lived in Stoupa and left an indelible impression in the mind of a budding author.

In “Report to Greco”, an ‘autobiographical novel’ written by Kazantzakis just before he died, he wrote about Zorba again and acknowledges the enormous impact that Zorba had made on his life.

“If it had been a question in my lifetime of choosing a spiritual guide, a ‘guru’ as the Hindus say, a ‘father’ as say the Monks at Mount Athos, surely I would have chosen Zorba.”

He tells us in the same chapter, of hearing the news of Zorba’s death in Serbia where he was running a ‘magnesite’ mine.

“…Zorba is gone, gone forever. The laughter is dead, the song cut off, the santir broken, the dance on the seaside pebbles has halted, the insatiable mouth that questioned with incurable thirst is filled now with clay, never will a more tender and accomplished hand be found to caress stones, sea, bread, women….”

A bronze bust of the author beside the road which also bears his name commemorates the time Kazantzakis spent in Stoupa and below this is Kalogria Beach where “Zorba the Greek” danced into legend.

“I had known much joy and many pleasures on that beach. My life with Zorba had enlarged my heart; some of his words had calmed my soul. This man with his infallible instinct and his primitive eagle-like look had taken confident

short-cuts and, without even losing his breath, had reached the peak of effort and had gone even further.”

Georgios Zorba (left) - The Mine Entrance/Flooded (right)

Georgios Zorba (left) - The Mine Entrance/Flooded (right)

The Office as it is now (left) - The Original Office (right)

The Office as it is now (left) - The Original Office (right)